Introduction

Over the course of its existence, the colonial Dutch Guianas experienced at least seven recorded slave rebellions, with each seeming to build upon the successes of the previous. But the 1763 Berbice Rebellion took control of most of the colony’s plantations and, for a short while, looked like it might actually succeed in forcing out the Dutch. This is all the more remarkable considering that it nearly predated by thirty years the Haitian Revolution, the only slave rebellion that actually overthrew a sovereign government. But only intervention by a combined force of British and Dutch merchant ships after months of uncertainty kept the Berbice governor from quitting the colony with the remaining colonists.

It might be considered a small miracle that the first successful slave rebellion did not happen in a Dutch-controlled colony. Due to the Netherlands’ lack of political cohesion and a decidedly frugal fiscal culture, they were particularly ill-suited to maintaining a slave society, and so entertained arguably the most pervasive slave-rebellion tradition in the Caribbean. The Netherlands’ founding Guyanese colonies of Berbice (1627), Essequibo (1615), and Demerara (1745, formerly a part of Essequibo) were originally privately owned, but were incorporated by the First Dutch West India Company after they acquired Suriname from England during the Second Anglo Dutch War.[1] Berbice, Essequibo, and Demerara were essentially more polished attempts to correct what was seen as some of the errors made by Suriname’s hale and hearty yeoman founders (Goslinga, 1985).

This article centers on the governor of Essequibo, Storm van s’ Gravesande, and his son-in-law Laurens Van Berch Eyck, the governor of Demerara, rather than on the governor of Berbice, Simon von Hoogenheim. Gravesande and Berch Eyck both expressed concern that the rebellion would spill over into their colonies. Indeed, a mini-rebellion did erupt in Demerara in which a group of slaves escaped during the chaos and bargained with Berch Eyck about whether they should remain loyal to the Dutch or possibly align with the Berbice rebels. The role that Gravesande and Berch Eyck played in organizing and planning an effective counterresistance should be a larger part of the historical record. My research demonstrates that the 1763 rebellion could have been more widespread than current scholarship dictates.[2]

At the embarkation of their colonial enterprise in the 17th century, the Protestant Dutch had already been engaged in an ideological war with themselves over the scrupulousness of slaveholding. The Germanic-speaking regions of Europe—including England, Germany, and the Netherlands—had been redefining their theological identity for the past century or so in the wake of the Protestant Reformation, wherein Martin Luther had initiated a wave of religious reforms in the Catholic Church in 1517. The First Dutch West India Company (DWIC) was established by Dutch Protestants who had been living in Catholic Belgium but had migrated north after the newly crowned Phillip II, a particularly hardline Catholic, had begun to repress them (Hoboken, 1982, pp. 131–132).

Both the Dutch East India Company (DEIC) and the DWIC were joint-stock enterprises designed to diversify the risk of transatlantic trading, but the DWIC in particular was principally established to harass and disrupt the trade that had made the Spanish formidable economic adversaries during the Eighty Years’ War (1568–1648). The most fanatically anti-Spanish voice in the Dutch leadership was a man named William Usselincx, who stressed the economic rather than the military importance of such a company. The Dutch may not have had the biggest army or the strongest navy in the world, but they could buy one if they had enough capital (Boxer, 1965, p. 106).[12] In fact, the Dutch turned to plantations as an investment after their efforts to break into the South American mineral trade were stymied by the Spanish—who had left few trade routes unexploited—and the rising price of sugar on the world market (Thompson, 1987, pp. 24–25). Thus, successful Dutch economic ventures helped the Dutch politically as well as militarily.

It seemed almost from Berbice’s beginnings that the undertaking of the slave complex would be rife with chaos. The Dutch colonial system maintained a prevailing philosophy that enslaved subjects would be more likely to submit if they had internalized the notion that their disobedience would be answered with the most horribly excruciating torture. These were epitomized by public displays such as whippings, the impalement of heads on pikes, the pinching off of pieces of flesh by red-hot pincers, or the hanging of victims by metal hooks through their ribs (Stedman, 1988, p. 67). Given this array of systemic atrocities, Dutch slaves looked for every opportunity for freedom. According to Jan Jacob Hartsinck, one of the colonial directors of the DWIC, issues with slave rebellions began as far as back as 1733, when a “rising of slaves” resulted in the death of two white servants. It was quelled. But in the year before the 1733 rebellion, the Second DWIC (the first had gone bankrupt) and a consortium of Dutch planters had signed the Berbice “Charter of Liberties,” which made the colony independent of the DWIC. The DWIC, skeptical of Berbice’s profit potential, franchised the territory out to the Van Pere family, who became its sole proprietors. But what must not be forgotten here is that the DWIC was administered in the metropoles of Zeeland and Amsterdam. These men living in the Netherlands had no connection to local Guyanese issues. And so, what was happening here was a somewhat significant transitioning from a metropolitan to a local government, which was much more interested in pursuing commercial slavery (Thompson, 1987, pp. 38–39). Now, the decline in social order that led to the 1763 rebellion is a little clearer. Two years after the 1733 revolt, Berbice suffered a military desertion of some sixteen soldiers. The next year, another slave rebellion occurred, the leader of which had his head impaled on a pike (Hartsinck, Pt. I; 1763; p. 35).

An examination of colonial Caribbean documents shows that the world planters wanted to reveal to their superiors was often not in accord with events they saw on the ground. They wanted their bosses, for instance, to believe that this tendency of slaves to run away was simply a matter of there being “good” and “bad” slaves. For example, many of the accounts of slave rebellions attest to how many “good” and “faithful” negroes were enlisted to track down the wrongdoers. One historian makes mention of “negroes from the estate who had remained faithful” tracking down “insurgent negroes” during a 1749 rebellion. (Hartsinck, Pt. I; 1763; p. 37) In the aftermath of the 1763 Berbice Rebellion, Essequibo governor Storm van s’ Gravesande attested to “faithful slaves,” (Gravesande, 1764) and during the manhunt following the Berbice Rebellion, official court records refer to “faithful Negroes” such as a Negro officer named LaBaum who was being sent out to capture one of the accused ringleaders (Berbice Court of Political and Criminal Justice, 1764). The tendency, then, to utilize the term “good” and faithful" to describe their slaves was part of the colonial imaginary, one in which a faithful slave did indeed have an immutable character—they were one of the “good guys.”

The truth, however, was far more nuanced. In the context of rebellion, slaves navigated their bodies and their families through violent assault and amongst continual inquiries into their political identities and notions of personhood. Most slaves in the colonial apparatus had to employ identities for both how they were perceived in the white world and how they were perceived in the black world. The stakes in how these identities were deployed were extremely high due to both the risk of severe controls that could be placed on bodily mobility and security in the colonial complex and the risk of isolation and exile from the slave community. And so, because of the intimate geography of the black and white worlds, and since spies have also been the downfall of many a maroon community and rebel plot, slaves had to keep their meta-identities fairly synchronous. And not only did slaves’ pursuit of personal autonomy depend on how they might deploy one of multiple situational identities to suit a particular context, their personal ideologies likely changed over the course of a lifetime, so one who might have identified themselves as a “rebel” in their youth, might define themselves as “faithful” in later years. So, most likely, slaves described as “good” or “faithful” by the Dutch had not in every instance of their bondage been so, and the fact that they were often enlisted to track down slaves who had already acquired their freedom likely increased the odds that they would be inspired to achieve their freedom sometime in the future.

Dutch authorities were well aware that once the “cancer” of revolution began to spread, it was extremely contagious. (Jordan, 1974).[12] But the highly arbitrary nature of the Dutch or British considering any slave “faithful” or “rebellious” suggests that many labeled “faithful” never truly considered themselves either, but were instead savvy social navigators who would always undertake the course of action that would provide them with safety, shelter, and food for them and their family. As such, there was rarely any one slave who was ever simply a “rebel” or “not a rebel.” Kenneth Stampp briefly touched on the complicated nature of the psyche of the oppressed when he noted that “a slave might reach the upper stratum of society through intimate contact with his master, by learning to ape his manners . . . as well as being a rebel or leader of his people.” (Stampp, 1989, p. 338) Stampp is suggesting that slaves were in a constant state of personal-identity negotiation, and the lines of rebellion might also shift within any one slave over the course of a lifetime. So even though a historian might label someone a “rebel” based on a chronologically fixed document, they might very well have no access to a record of what this “rebel” might have done the next day, such as jovially washing her mistresses’ clothes while ruminating on the previous night’s slave-quarter conspiracies. During the Berbice Rebellion, both masters and rebels were engaged in a struggle for control of slave bodies, as they knew that access to bodies meant access to information, and access to information was the key to victory. It was the savvy social negotiator who could exploit the fact that what they brought to the table was far more than slave labor—a great degree of power lie in the knowledge that with slave allegiance came de facto control of the land. This would partly depend on the ability of African slaves to shift from “faithful” to “rebel” identities—performing along a sliding scale of political economy gauged by the increasing and decreasing dynamic of how much trust the colonial powers were willing to invest in them. The more trust a slave was invested with, the more mobility they accessed and the more use they could be to insurgent slaves. Slaves had to slide stealthily along this scale, however, as the Dutch chose to compensate for their low population numbers with ferocious acts of terror.

February, 1763

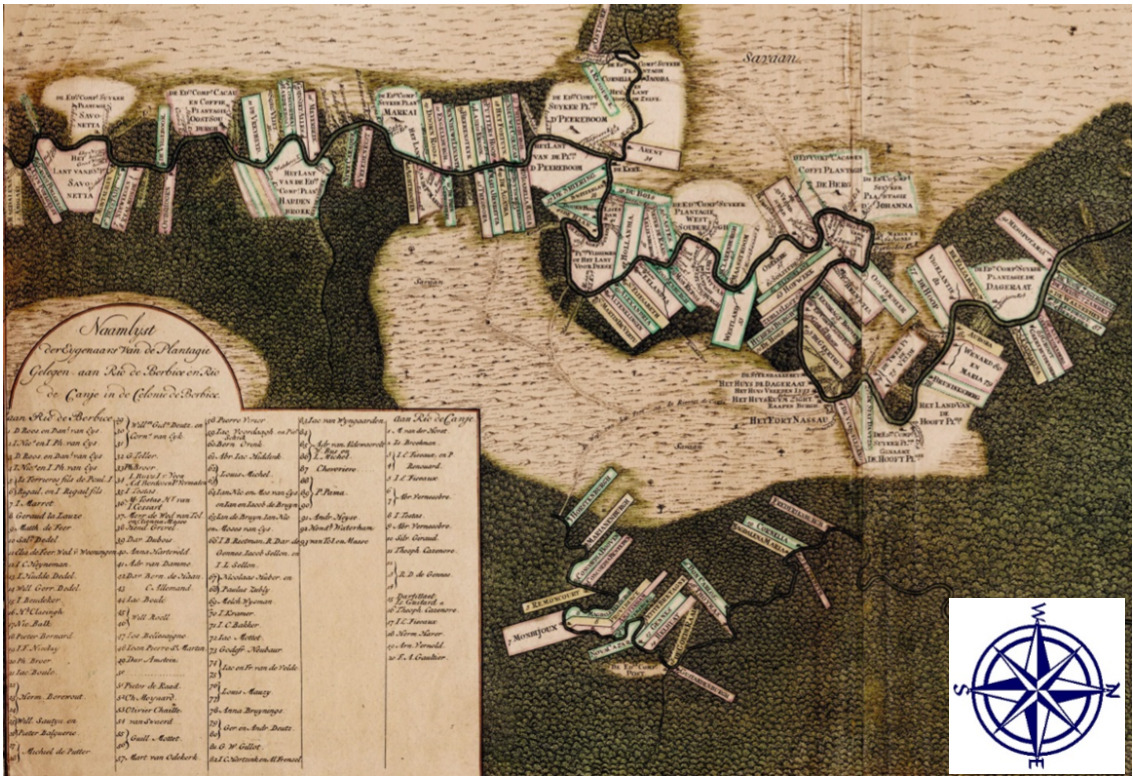

Berbice was comprised of two river settlements: one on the Berbice River, and a smaller, more sparsely populated one on the Canje River, to the east. The Berbice Rebellion ignited in both of these two theaters of conflict. Of the first to occur, there is little debate.

It was on the Canje River’s Plantation Magdaleenburg that the Berbice Rebellion began on February 23. But the rebellion could have been considered fairly minor and under control had it also not erupted on the Berbice River four days later, on February 27. Once the two rebellions combined their forces—which they did, soon after—they presented a stronger force than the colonial administration had resources for. There has been considerable disagreement as to which plantation was the origin point of the rebellion in the Berbice Theater. Alvin Thompson, the foremost authority on slave rebellions in the Dutch Guianas, wrote, “The plantations usually associated with the early phase of the Berbice revolt are Lilienburg, Juliana, Hollandia, Zeelandia, Elizabeth, and Alexandria. The first four of these have been variously put forward by different writers as the eye of the storm, but the evidence on this score is quite patchy at present” (McGowan et al., 2009). From Cornelis Goslinga, the famed Dutch historian, we have only this: “On February 28, the slaves of five plantations along the Berbice River murdered the whites of these, and plundered and burnt most of the buildings” (Goslinga, 1985). Jan Jacob Hartsinck, the Dutch West India Company official and historian, published a history of the events seven years after they happened (1770) and claims that the rebellion in the Berbice River Theater began on Plantation Juliana: “From there, the fury passed over to MonRepos and Essendam.” (Hartsinck Pt. 1; 1763; p. 39). Marjoleine Kars concludes that it started on the Plantation Lilienburg. This is based on testimony the year after the rebellion (1764) of a slave driver named Cupido, who had betrayed the plot to the Dutch (Kars, 2020). Cupido lived on Hollandia, so his account is more than likely the most dependable account of the three because the testimony is contemporary with events and Cupido actually lived in the area.

The letters of Demerara governor Laurens van Berch Eyck and his father-in-law, Essequibo governor Storm van s’ Gravesande, provide an alternate theory, however: On March 12, 1763, Gravesande reported that “on the Plantation Monrepos, Ian Michael Snyder, the ensign, major Daniel Luxemborg, and the Surgeon Del with his wife were murdered” (Gravesande; March 12, 1763). On March 27, Berch Eyck related a report of considerably similar detail: “I have learned of the unpleasant news from our neighboring colony of Berbice through one Gerhard Lammert . . . [It] began on the 27th of February, when the blacks on the Plantation Monderpoel killed I. M. Snyder, the city ensign, the Surgeon Major D. Luscenburg, and the Surgeon Del” (Berch Eyck; March 12, 1763). It was often the case that plantations were known by more than one name, particularly if they had had more than one owner. The similarity of the narratives strongly suggests that “Monderpoel” and “MonRepos” were the same plantation. There is no “Plantation Monderpoel” on the Berbice map of plantations found above, but there is a “Plantation MonRepos” located right between plantations West Souburgh and Roosenburgh, right in the center of where Kars, Hartsinck, Goslinga, and Thompson all say the rebellion began. Although Cupido was a primary source, his account was taken the next year. Gravesande’s and Berch Eyck’s accounts, recorded within weeks of the rebellion, could be considered another credible possibility as to where the rebellion began in the Berbice Theater: Plantation MonRepos.

March

On March 17, Essequibo governor Gravesande initiated an international rescue effort that was aided and abetted by his son-in-law, Demerara governor Berch Eyck, as well as Suriname governor Wigbold Crommelin. Gravesande wrote a March 17 letter to the British colony of St. Eustatius, where he tried to appeal for help against the rebels.[12] Gravesande’s letter was explicitly to “give notice of the sad reports coming our way out of Colonie Berbice.” In the letter, Gravesande indicated that he would also be writing to Barbados, another British colony, for help (Gravesande; March 17, 1763). This is not as surprising a move as it might seem. When the British traded Guyana to the Dutch for New York at the end of the Second Anglo Dutch War, many British planters retained their interests in Guyana plantations. Gravesande knew that if he appealed to the British slave plantation of Barbados and apprised them of the situation, he would get a much faster response from people who wanted to protect their assets than waiting for the glacial deliberations of the DWIC’s always-frugal Nineteen Lords (XIX Heeren). Here was a classic example of the transnational slave-holding class ignoring national rivalries in order to protect common financial interests.

Berch Eyck’s gamble with the letters paid off. On April 7th, a warship, on April 9th a privateer, and on the 11th another warship appeared in Demerara. In this case, however, the ships were there solely to protect Demerara plantations owned by British citizens from the rebellion’s spread. Indeed, once the rebellion began, its spread seemed to be a constant concern to Berch Eyck and Gravesande. And perhaps with good reason. There is a longstanding debate as to whether or not slave rebellion was caused or inspired by the enslaved hearing about the successes of other slave rebellions. [12] Perhaps slave rebellion was a function of slaves recognizing the political and social fissures that other rebellions revealed in the power structure of their white oppressors. What resistance might need to make it a palatable option is for the enslaved to see a reasonable chance of success, and that most often occurs at a point in which they recognize that there is a fraught tension in the political superstructure that can be exploited into an avenue of escape. This notion of “avenues of escape” is one that has been suggested by several resistance scholars, but seldom articulated as an analytical framework through which we can actually quantify and predict resistance. But several times in our narrative we will see that as soon as the administrative framework shows gaps in its superstructure, some attempt at freedom occurs soon after. This seems to indicate that many slaves did recognize avenues of escape in the colonial superstructure, and were proactive and savvy enough to exploit them.

Kars claims that Berch Eyck acted swiftly to secure Demerara, but much evidence points to the notion that he might have had more difficulty than he had anticipated (Kars, 2020, p. 98). Berch Eyck himself wrote a letter on April 8 stating that he had received word on March 17 that the rebels had intended to attack Demerara on March 28 (Berch Eyck, March 17, 1763). At that point, Berch Eyck himself related that he wrote to the Directors General for aid. Then, on March 23, Berch Eyck reported an event that would soon have great consequences for all colonies: a local slaveowner had acquired an “oath, that [recaptured rebels]” from Demerara’s Plantation the Bell and Plantation Bermingham “would inform on troublemakers, put them in handcuffs, and deliver them” to Berch Eyck. Many of the slaves from the Plantation Bermingham had been committing acts of petit maronnage, in which slaves would go out in to the bush and send representatives back to their home plantations to negotiate about their further treatment.[12] This phenomenon also occurred more frequently when acts of rebellion had occurred nearby. Indeed, acts of petit maronnage were not merely instances of frightened slaves running to the woods to hide, but occurred often after slaves had made a premeditated determination that, at that particular time, there was a reasonable avenue through which they could make good their escape to a new reality. Now that the rebellion in Berbice had broken out, some of these enslaved men and women from Demerara could possibly have brokered a deal to turn in any suspected slave rebels. Berch Eyck could have either punished these slaves severely for running away in the first place or he could have struck a deal. The Demerara governor chose the latter path and had the slaves join a contingent of slaves tasked with keeping his colony from also breaking out into rebellion.

Four days later, on March 27, Berch Eyck would learn that the crisis on the plantations Bermingham and the Bell was just beginning. He received a letter from Demerara plantation-owner Isaac Knott which indicated that the slaves on the Bermingham were preparing to desert, despite their earlier agreement (Berch Eyck; March 29, 1763). Soon after, Berch Eyck sent “30 Criools armt” to help “in taking the Rebells.” Kars mentions that Gravesande and Berch Eyck “assembled a small army of thirty’ trusted Creoles,'” but notes only that they were assembled “to quell rumored slave unrest upriver” (Kars, 2020, p. 99). That slave unrest was indeed on the Plantations Bermingham and the Bell, and it was more than a rumor. Knott’s March 27 letter suggested a dual-plantation conspiracy. He noted that on the same day that they noticed that some Bermingham slaves had not reported home, “fifteen slaves . . . this morning ran away from the plantation the Bell.”

Berch Eyck’s monitoring of the situation in Berbice was now in its fullest engagement. Indeed, the amount of mobilization it caused in Demerara makes it seem as if it should have been considered a colonies-wide revolt. In a March 30 letter, he noted that he had “convened the government to speak about [the Berbice Rebellion], and what rules to devise that would be helpful for our river until such a time as they, God forbid, reach us by coming over” (Berch Eyck; March 30, 1763). The next day, March 31, the plan became clearer. Berch Eyck received news that “Bermingham’s negroes along with those from the Plantation the Bell between Sunday and Monday ran away to Creek Maboelissa” (Berch Eyck; March 30, 1763). Gravesande’s statement that the Bermingham plantation was on the upper reaches of the Demerara and the fact that we know that Berbice rebels held the most dominant position upriver further strongly suggests that slaves from plantations Bermingham and the Bell took the opportunity of the Berbice Rebellion to put plans for their own escape into effect, just as governors Berch Eyck and Gravesande feared. At this point it is clear that Berch Eyck fully expected the Berbice Rebellion to spill over into Demerara unless he took immediate action. The Bermingham-Bell Rebellion might have suggested to him that Demerara’s slaves were looking for avenues of escape in order to capitalize on the spirit of rebellion spreading from the east.

Shortly after the 1763 Rebellion began, a group of colonists put together a petition importuning Berbice governor Simon von Hoogenheim to allow them safe passage back to the Netherlands. Listed among their complaints was their realization that, “some of our mulattoes and negroes who have thus far been faithful, knowing the arrangements inside the [severely compromised] Fort [Nassau], are now absent and have become unfaithful and quitted” (Hartsinck, Pt. II, 1763, p. 40). But while many of the slaves during the Berbice Rebellion made a conscious choice regarding whether to take up an identity as a rebel, some had that identity thrust upon them.[12] On an expedition up the Canje River undertaken by Skipper Michliel Ramelo in late March of 1763 to salvage plundered plantations in war-torn Berbice, Ramelo encountered some slaves who were most likely hiding from the chaos. Evidently either unaware of their allegiances or simply uninterested in determining them, the skipper shot at the slaves, whereupon they subsequently took to flight (Hartsinck, Pt. III; 1763; p. 45). Given that both colonists and slaves had been awaiting rescue by Dutch ships in the wake of the revolt, few would have been able to blame these slaves if they would have subsequently made their camp with the rebels.

April

On April 10, a G.F. Brouwer reported to Berch Eyck that after “two of his hunters yesterday around five o’clock were assaulted by five large Negroes . . . this morning between three and four o’clock heavy musket shots were heard upriver” (Berch Eyck; April 9, 1763). So not only might the Berbice rebels have entered Demerara territory, it seems they were armed and confrontational. This would correspond with another communique from Berch Eyck that stated that the Berbice rebels openly proclaimed to Berbice officials that “once their ammunition ran out, they would come to Demerary to get it from there” and that the postholder was said to have “speedily retired, as the mutineers have resolved to murder him, so that he could not warn them if they came to the river” (Anonymous; April 11, 1763). By May 9, Berch Eyck was convinced that “the rebels could easily come over here” (Berch Eyck; May 9, 1763), and by June 12 knew enough about the enterprise to comment that “the way over Karrekarre [Creek] is easier for the rebels” (Berch Eyck; July 13, 1763).

Although there is no evidence of verbalized complicity between whites and rebels, many of the actions of the proprietor of Demerara’s Bermingham plantation during the Berbice Rebellion raise questions. On April 3, 1763, for instance, Demerara governor Berch Eyck reported in his journal that “Mr. E. Bermingham has prevented the creoles from catching the rebels who were at the plantation” (Berch Eyck; April 3, 1763). Two days later, it seemed that Bermingham’s obstinacy only escalated, as “the Commander again went upriver with his assistant to give the order that if not followed willingly then it should be enforced with violence, and that if Mr. Bermingham does not want to hand them over or let them go, he would also be taken prisoner” (Berch Eyck; April 8, 1763). By April 8, it seems that Bermingham had forced the hand of the Dutch authorities, as Berch Eyck received news that “Mr. Bermingham, with all of his people, have been taken prisoner” (Berch Eyck,; April 8, 1763). The term “his people,” seems ambiguous as to the identity of the captives, however. Were these people friends and family of Mr. Bermingham who were actually colonial citizens? Not likely. A subsequent entry from Berch Eyck confirms that included in the congregation Bermingham was protecting were “prisoner slaves” (Berch Eyck; April 9, 1763).

Letters written by Essequibo governor Gravesande two months after the Bermingham incident give further details on Bermingham’s actions. A letter written in May notes that when trusted slaves tasked with the responsibility of finding rebels arrived at the Bermingham Plantation, they showed Mr. Bermingham a written command, whereupon he “refused immediately to leave from the plantation, saying his people had no need, with many unbecoming expressions which no white witness should consider” (Gravesande; May 2, 1763). An October letter further details that when Bermingham refused to leave his plantation, he actually subsequently “ordered [the creole] to abandon the plantation, which he did.” On succeeding days, Bermingham “with a yacht and a canoe went sailing in the face of an oncoming vessel with a soldier standing on guard, not answering after three calls, whereupon he was told that if he did not answer it shall be to his peril.” When a commanding officer named Vleeshouwer later questioned him as to the whereabouts of the rebels, Bermingham replied that he did not know. But when reminded of the orders from the commander to turn in rebels, “he impertinently answered in the French which was spoken ‘I don’t care for the orders of your Commander! (Je me fou des orders des Commander!)’” Gravesande reports that the main commander in Demerara had been telling residents that if the Bermingham rebels were not captured, then “all would be lost,” and that they were already off to another plantation to “stir up” the slaves there.[12]

In an April 12 letter, Essequibo governor Storm van s’ Gravesande indicted a multicultural coalition of participants in a rebellion plot in his colony. In it, the governor cited that the complicity of “the resident Jan La Tureve with his Indian,” “a Criole of Mr. van Doom’s,” and a “Negro of the Widow de Bruyn” caused “great consternation” due to their role in the rebellion, as they were “the least suspected” (Gravesande; May 2, 1763). In November of that year, Berbice governor Simon van Hoogenheim revealed further confirmation that some whites had identified with the black struggle for freedom with his mention that “the Negros in Canje had three whites with them, who with them left to Berbice, to the other rebel Negroes, where they jointly defended it against the Christians” (Hoogenheim; November 20, 1763). Could Mr. Bermingham sympathized with or even have been a part of these events?

May

In a May 2 letter, Gravesande noted that British official and Demerara planter Gedney Clarke from Barbados had responded to Gravesande’s earlier plea for help with a warship and seventy-five men. The warship proceeded to capture six Bermingham rebels. While this action is again one in which European slaveowners overlooked national differences to ensure mutual interests, it also reveals something more: During Clarke’s mission he uncovered evidence that implicated three more whites.So not only could Bermingham have been a part of a multicultural slave communication network, he seems to have been involved with other whites who were in cahoots with black rebels. The rebels were continuing to employ a resistance strategy wherein groups of ambassadors would go from plantation to plantation soliciting help. Gravesande claims that “three or four of the Berbice mutineers came over to stir up the slaves by showing the good results of their undertaking” (Gravesande; May 2, 1763).

Gravesande’s May 2 letter also notes that on the warship that Clarke brought from Barbados was a letter from the governor of St. Eustatius. It mentioned that he too would be sending two vessels to Berbice to help with the slave rebellion. Gravesande also received a bit of intelligence that suggested that he had a source in the rebel camp. A man named Goederhand notified the governor that the mutineers from Berbice said[12] that “if their ammunition was lacking, they should come and get it in Demerara” (Gravesande; May 2, 1763). This seems to suggest that the slave rebels had not only established a reliable communication network from Berbice to Demerara, but had secured a weapons-supply route. A Berbice Colonial councilmember named L. Abbensetts seemed to confirm this information in a May 13 letter and Demerara governor Berch Eyck somehow also confirmed the existence of this route in a letter he wrote a week later. The armed support he received from St. Eustatius, however, seems to have caused as much consternation as relief. In his letter, Berch Eyck expressed fears that once “two armed vessels from St. Eustatius arrived in Berbice to fight the rebells, by that occasion it could happen that those rebells would come to this River—therefore I think it would be very good that Capt. Herbert should go up with his armed brig to [Demerara’s] Maboelissa or Karrekarre Creek” (Berch Eyck; May 10, 1763). On May 18, the remaining members of the Berbice Colonial Council gave a bit of insight into the rebels’ Berbice-Demerara network. According to a Demerara postholder, the Berbice slaves had “an old slave leader from a Society’s [DWIC] plantation,” presumably a Demerara slave, who was giving Berbice rebels access to supplies (Hoogenheim, et al; May 18, 1763).

On May 25, Suriname governor Wigbold Crommelin sent three officers and fifty men to the Courantyne River, the border between Suriname and Berbice, to help Berbice governor Hoogenheim. With this, the fourth of the Dutch Guianas’ four colonies had now been mobilized.

June

In a letter Suriname governor Crommelin wrote on June 2, he admitted to worrying that the political environment that the rebels had created during the Berbice Rebellion would coalesce into legitimate rogue states, further destabilizing his colony’s neighboring maroon community: “The rebels have come . . . to the Courantyne and they and their followers with the people there prevented a defense to form, to row out in combined might because it would not only be very dangerous for Berbice but for us all should they make a free state with the people there or with the Indians” (Crommelin; June 2, 1763).[12]

August

In an August 22 letter, Essequibo governor Storm van s’ Gravesande claimed that “good-willed slaves who remained hidden on their plantations” would be “saved and protected” (Gravesande; August 22, 1763). By August 30, it seems like the onslaught of armed barks from St. Eustatius and Barbados, combined with cadres of dangerous Amerindians, began to convince more slave families to “defect” (overgelopen) back to the Dutch side, to use Berch Eyck’s terminology. On that day, he eported that Hoogenheim received twenty-two creoles who had previously taken up with the rebels. Berch Eyck makes a point of stating that among these defectors were “men, women, and children,” suggesting that families had been waiting out the conflict to see who would end up with the upper hand. In the waning days of the rebellion, Hartsinck also noted that “now and then, there came various negroes with their wives and children . . . to surrender voluntarily.” Nearly all the accounts during the early part of the rebellion reported that slaves repeatedly vanished into. the bush once a Dutch ship came by. But once the Dutch received reinforcements it was reported by Berbice governor Hoogenheim that “no more rebels were to be seen in the neighborhood” and that rogue slaves were “standing at the waterside begging to be taken over, as they were well-intentioned slaves who had committed no wrong.” Most of these subsequently claimed that the rebels “had forced them into their power” (Hartsinck, Pt. VII; 1763; p. 60). But a sophisticated game of identity politics was most likely at work. Say, for instance, a slave who was very adept at deploying a “faithful” identity encountered a rebel cadre possessing the food and blankets his family needed. Could that not account for Hartsinck’s claim that “the most faithful slaves have come under the influence of [the rebels’] conspiracy?” (Hartsinck, Pt. II; 1763; p. 38).

October

A letter from Essequibo governor Gravesande on October 13 suggests just how devastating the Bermingham-Bell Rebellion was to Demerara. According to Gravesande, all the whites from upper Demerara had fled to Essequibo due to the continued presence of rebels in the area and he was receiving message after message for help. The Bermingham-Bell rebels had previously travelled to Berbice, but now they had come back and the “young Bermingham,”—presumably Bermingham’s son—made Gravesande “solemnly promise to deliver the rebels in hand.” The fact that the Bermingham-Bell rebels travelled to Berbice lends credence to the theory that they might have also had come degree of collusion with the Berbice rebels before either rebellion began. The plan could have been to resupply, in fact, at Plantation Bermingham, which Gravesande here described as “in the utmost angst and danger” to colonists. The younger Bermingham here seemed to be working with Dutch authorities to secure his birthright. Soon enough, Gravesande sent “the speediest well-armed Creoles, a subordinate officer and some soldiers to Demerara” (Gravesande; October 13, 1763).

Gravesande also voiced fears in that same letter that the Berbice Rebellion could degenerate into the same kind of political morass as experienced by Suriname governor Wigbold Crommelin. Crommelin had given up on recapturing maroons and actually negotiated treaties with them in 1760 and 1762, stipulating that the raids to recapture them would stop in exchange for the promise of the maroons to stop raiding plantations for food, supplies, and more slaves—which they had been doing at every opportunity—and that they would return subsequent fugitives to the Dutch. Concerned that his forces would not be able to repel a rebel attack, Gravesande admitted that “if the Rebels retreat to this side freely held, they will be able to strike against all from the upriver to below, thus being able to outlast us, and this will become a retreat for our evil-willed slaves, such as the people of Suriname have found” (Gravesande; October 18, 1763).

March, 1764

By March 1764, Barbadian official Gedney Clarke wrote a letter to the directors of the DWIC’s Zeeland chamber that the “Cruel rebellion at Berbice” had been “quelled,” and he notes that the slaves in Demerara, where his financial interest was staked, were “kept in awe” by the “steadiness of the inhabitants.” It is difficult to surmise what Clarke could have possibly meant by “kept in awe,” as the Bermingham-Bell Rebellion in Demerara clearly suggests that the slaves there were at least inspired by, if not complicit with, the courage of the Berbice rebels. And “steadiness” must be a relative term,[12] as Gravesande had already reported that “all the whites from upper Demerara had fled due to the continued presence of rebels in the area.” Clarke continues with what can only be seen as a bit of fanciful speculation. He surmises that if the colonial inhabitants of Demerara had deserted their habitations as those of Berbice did (which, we know, they did), then “the River Essequibo would now have been in the possession of those merciless savages” (which, we know, did not happen) (Clarke; March 20, 1764). It was in fact the aggressive actions of governors Gravesande and Berch Eyck to call for reinforcements that forestalled such a circumstance.

It was not until December of 1764 that one could say that the Berbice Rebellion was back under Dutch control. Around this time, the Dutch issued a “general amnesty or pardon to the additional and remaining Negroes” in the colony:

All those who hear or read this should know that we, after long deliberation, have found and resolved that, regarding all Negro slaves, men as well as women, who during the general revolt of Negro slaves in this colony hid and without impunity remained without further interviews from sworn rebels . . . are granted pardon and forgiveness with the serious stipulation that they themselves shall thenceforth actually serve their masters with greater obedience and good faith, and that they should be unwilling to go against this directive, and shall hold themselves up as brave and faithful Negroes, or they shall be punished with bodily pain (Berbice Colonial Council; December 12, 1764).

So here we see the narrative the colonial government has chosen to construct for slaves seeking refuge and the parameters under which they might safeguard their lives. The Dutch allowed for “faithful” slaves hiding in the bush for a year and a half, eschewing all contact with rebels, to be welcomed back into the fold of Western hegemony. The administrators knew that there was a possibility some slaves might have been ideologically led astray, however, and possibly committed some crimes, so the slaves herewith had to make a solemn affirmation and pledge to thenceforth serve their master “with greater obedience and good faith.” With this directive, the Dutch made their point. They were really not as much concerned with what these slaves had been doing as they were with whether or not they were going to be faithful to their masters after the rebellion. And if they would hereby swear to serve them with even greater obedience than before, that would be even better. For slaves, the construction of alibis was in full swing, with the open knowledge that the majority of people who might be able to contest your alibi would soon be arrested and executed. Once the rebellion was quelled, the exact same enslaved people were in the colony who had been there before; the only difference is that they were telling their new (old) hegemony what they needed to hear in order to be accepted back into the new (old) order. In essence, everything was to go back to how it was before the rebellion, but this time with a promise to never rebel again.

One must question many of the terms used to characterize slaves in the context of rebellion. Can we now trust that these slaves were “good” in the way the Dutch would have interpreted “good,” as those who remained faithful to the Dutch cause? The rogue slaves standing by the waterside described by Gravesande claimed that they had “committed no wrong.” And they were in fact telling the truth—because “wrong” would have been anything that would have led to their deaths. Hiding for months in the bush waiting to be rescued by a Dutch ship, or going over to the rebel camp while waiting to see how the rebellion turns out would by no means by their standards be considered “wrong.” Indeed, it was the only course of action that would have been “right.” Although a slave’s true loyalty might be influenced by external factors such as interests, values, or prior experience, the identity they represented to the world could have remain unfixed. The savvy social negotiator had the capacity to use deception and guile to slip between identities—indefinitely, or until they were forced to choose a side. Their loyalty would be then, in a sense, contingent on which side—rebels or owners—could best guarantee their survival and access to social reproduction. Those who retained enough anonymity in both spheres of power that they could switch from one side to the other had already made the choice to deny their rebellious identity and re-appropriate one of a slave who had been forced to join the rebels against their will. Contemporary accounts suggest that the majority of slaves exercised this “contingent” loyalty, with a minority comprising “extremist” rebels or servants. As such, once the rebellion started to tilt towards one way or another, large and small groups of slaves would start to commit to the winning side—in a court trial, or even at the point of a zealous boat captain’s gun.[12]

We cannot presume to think the Dutch were unaware of the fact the slaves they were reintegrating into their colonial system might have been fighting as rebels the week before. Note Hoogenheim’s policy of general amnesty—it would have been far more expensive in effort and lost property for the Dutch to prosecute and possibly execute all who had defected than it would have been to simply accept the tales of kidnapping. Even Hartsinck seems to acknowledge as much, with his wry claim that “the power of the rebels was dwindling continually.” “The power,” —not the numbers. His claim that “the River below the late Fort cleared of rebels and these being scattered apart so that their reassembly in really large numbers was rendered impossible” suggests that by this point there was a mass of “rebels” still out there, watching, waiting, plotting; rather than adroitly switching sides and coming out to the riverbanks (Hartsinck, Pt. VII; 1763; p. 61). “Large numbers,” indeed. All but the most hard-core insurgents had long since switched identities. One could imagine this process going on until there were no more actual rebels extant, while the search for them, ever-vigilant, ever-comforting, continued upriver in earnest.

For more on how poorly the Dutch planned their colonial enterprises, see C. R. Boxer, The Dutch Seaborne Empire: 1600–1800 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1965); Pieter Emmer, The Dutch in the Atlantic Economy, 1580-1880 Trade, Slavery, and Emancipation (Aldershot: Ashgate Variorum, 1998); Gert Oostindie, ed., Dutch Colonialism, Migration, and Cultural Heritage (Leiden: KITLV Press, 2008). These books are not the definitive authority on the Dutch experience, but they all strongly imply that Dutch attempts at colonization were largely done in reaction to Spanish aggression after the Eighty Years’ War.

It must be noted that although my research was done in an English-speaking country, the bulk of the documents I draw from were all written in Dutch. I feel this must be mentioned because one reviewer for a book manuscript I submitted lamented that they did not think I read Dutch, perhaps because of where the archives were and because my name is not Dutch-sounding. I took two years of Dutch and did an independent study with Indiana University Dutch expert Esther Ham during my Ph.D. program expressly for the purposes of translating these documents. As such, the translations are not perfect, but they are mine and they are fairly reliable.

This term is borrowed from Jordan’s formulation that slave revolution often spread like cancer when slaves heard about other successful revolutions.

There is an entire field of scholarship on how the enslaved spread news across the Caribbean during the colonial era. Colonial powers did their best to control the flow of information between each other, but racial prejudice led many to miscalculate the comprehension abilities of their enslaved servants and reveal secrets and sometimes even tactical information in front of them. For more on this in the Caribbean, see Michael Craton, “Proto-Peasant Revolts? The Late Slave Rebellions in the British West Indies 1816 – 1832” Past & Present No. 85, (Nov. 1979), p. 101 – 105; 110 - 117; James Sidbury, “Saint Domingue in Virginia: Ideology, Meaning, and Resistance to Slavery, 1790-1800,” Journal of Southern History, Vol. 62, no. 3 (Summer 1997), p. 534, 538; Laurent Dubois A Colony of Citizens: Revolution & Slave Emancipation in the French Caribbean, 1787-1804 (University of North Carolina Press, 2004), p. 60, 90, 230, 235 and Dubois Avengers of the New World, p. 164; C. L. R. James, The Black Jacobins, p. 82 – 83; and Emilia Viotti da Costa, Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood: The Demerara Slave Rebellion of 1823 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), p. 43, 61, 178 – 179. The most comprehensive and definitive work on this topic in Caribbean historiography is W. Jeffrey Bolster’s Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997).

On the fear (often substantiated) that slave rebellions often sparked other slave rebellions nearby, see Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1998); Jacob R. Marcus and Stanley F. Chivet, eds., Historical Essay in the Colony of Surinam, 1788 (New York: Ktav Publishing House, 1974); Eugene Genovese, From Rebellion to Revolution (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1979*)*; Matthew Guterl American Mediterranean: Southern Slaveholders in the Age of Emancipation (Harvard University Press, 2008); Goslinga The Dutch in the Caribbean and in the Guianas, 1680-1791. Colonial administrators rightly surmised that often when slaves heard about other slave rebellions, it gave them either inspiration, instruction, or opportunity to initiate their own revolts.

For more on petit marronage, see Herbert Aptheker, American Negro Slave Revolts (New York: International Publishers, 1943), p. 142; Vincent Harding There Is a River: Black Struggle for Freedom in America (New York: Vintage Books, 1983), p. 199; Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004), p. 36, 39, 87

For more on the ways in which enslaved persons shifted their identities in order to negotiate the European slave complex in the Caribbean, see Walter Johnson, Soul to Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market (Harvard University Press, 1999), p. 150; Berlin Many Thousands Gone, p. 17, 62, 104, 174- 175, 255, 325; Ada Ferrer, Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868–1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1999), p. 68; and Jane G. Landers, Black Society in Spanish Florida (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1999), p. 56.

Where I use the term stir, Gravesande uses the Dutch verb stoken, as in “to stoke a fire.” Because thinkers like Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Voltaire, Denis Diderot, and Baron Montesquieu were all French, many colonials associated the natural-rights philosophy, which these men were known best for, with France. The natural-rights philosophy argued that mankind’s rights did not emanate from the state, but in fact were given to all people at birth. For more on how this philosophy influenced and even inspired slave revolts, see Stephanie Smallwood, Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), p. 138, 143, 183; Sidney Mintz, Caribbean Transformations (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989), p. 25; Leon Litwack North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States, 1790 – 1860 (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1965), p. 61; Lorenzo Greene, The Negro in Colonial New England, 1620 – 1776 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942) p. 258; David Jamison “New World Slavery and the Natural Rights Debate” Journal of Caribbean History Vol. 49, no. 2 (2015)

“hebben gesegt”

The Suriname maroons were far and away the world’s largest maroon community. Spreading some sixty miles from the northern coast of South America in to Suriname’s interior, these descendants of slave rebels comprise at least six distinct ethnic minorities, each with a distinct dialect and culture borne from the first settlements in the 1760s. For more on the Suriname maroons, the work by Sally and Richard Price is indispensable, especially Maroon Arts: Cultural Vitality in the African Diaspora (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999) and First-Time: The Historical Vision of an Afro-American People (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983). The Prices are anthropologists, not historians, who spent a great deal of their field work with the Suriname maroons. No other scholar really comes close to their level of firsthand knowledge about maroon culture.

Clarke was British, so “steadiness” is the literal word that he used, rather than my translation.

There is substantial scholarship on the issue of “faithful” slaves collaborating with colonial agents to oppress their peers and perpetuate the slave system. The most comprehensive work on the topic of African collaboration with European colonists in general is the edited volume Intermediaries, Interpreters, and Clerks: African Employees in the Making of Colonial Africa (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006). Although focused on Africa, this volume analyzes a variety of collaborationist scenarios. Other selections include Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005) p. 8; John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community: Plantation Life in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 1972), p. 100, 115, 135 – 138, 189 – 193, 200, 208; Deborah Gray White, Ar’n’t I a Woman: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., 1999), p. 24, 176; Herbert Gutman, The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom, 1750 – 1925 (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976), p. 93; Michael Craton, Testing the Chains: Resistance to Slavery in the British West Indies (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2009), p. 35; and Perry Kyles “Resistance and Collaboration: Political Strategies within the Afro-Carolinian Slave Community, 1700 – 1750” The Journal of African American History, Vol. 93, no. 4 (Fall 2008), p. 499. All of this scholarship raises the issue of motivations. Did collaborators truly feel an affinity for their Western oppressors? Had they fully internalized the concept that Europeans were culturally superior? Or did these people in fact simply manipulate Westerners into thinking they were faithful, while all the time prioritizing the safety and well-being of their families?